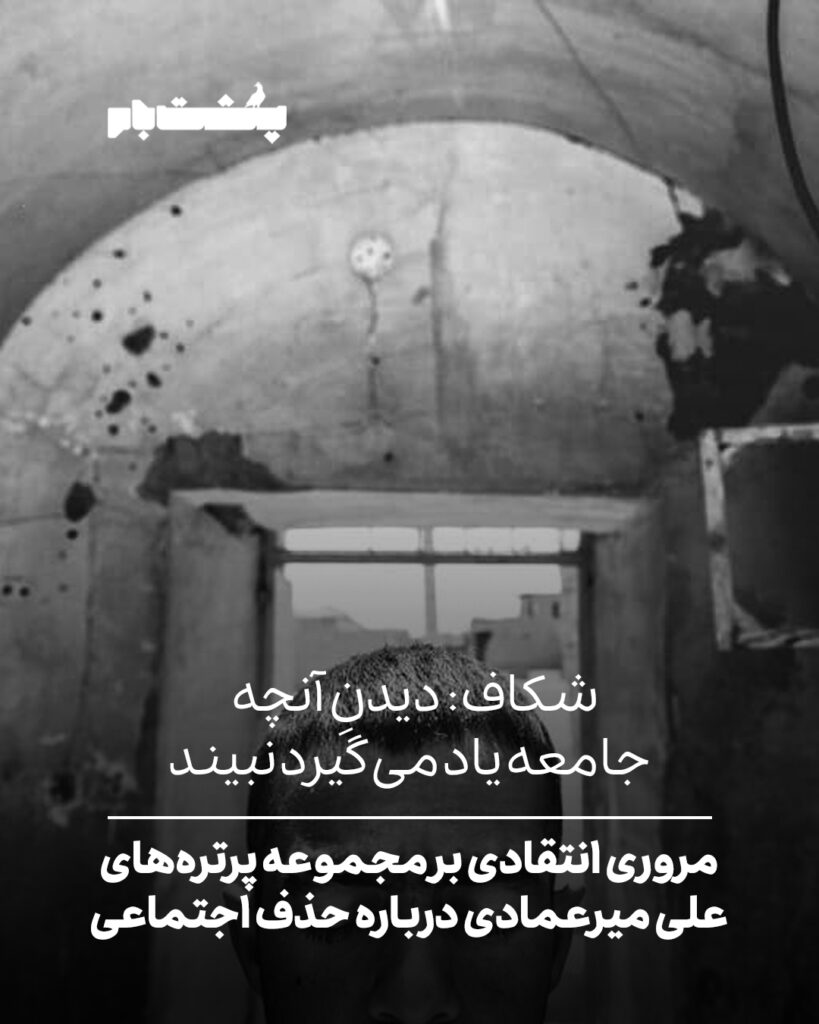

مروری انتقادی بر مجموعه پرترههای علی میرعمادی درباره حذف اجتماعی

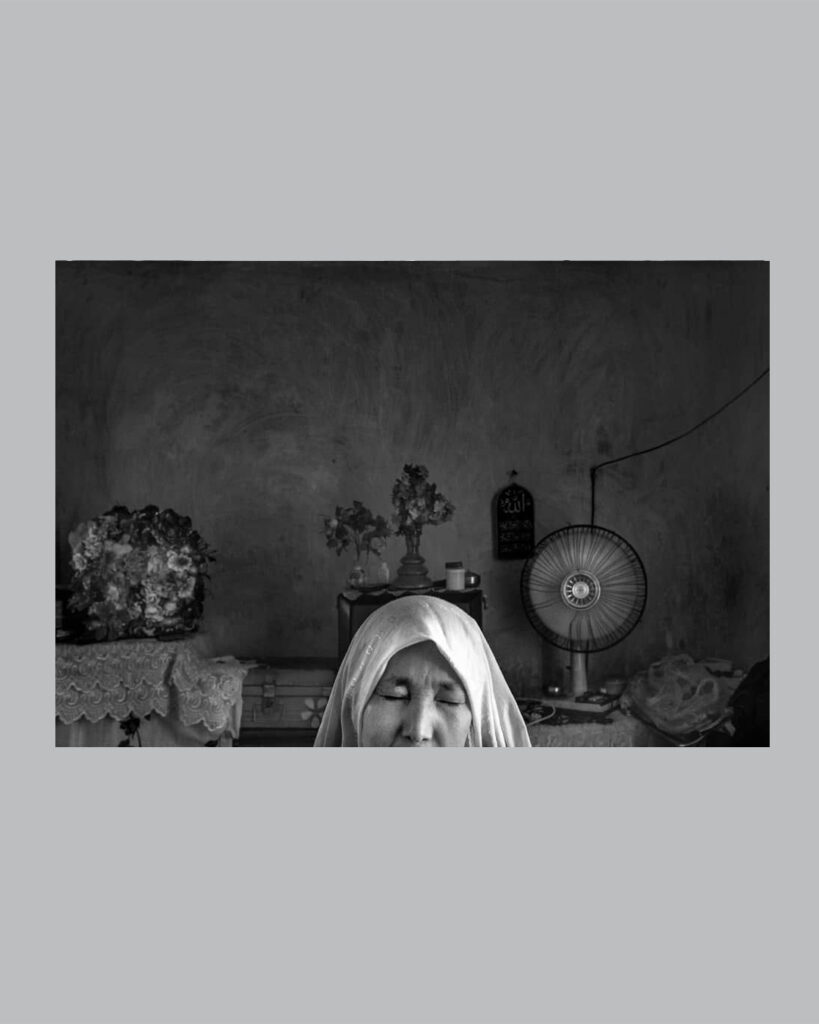

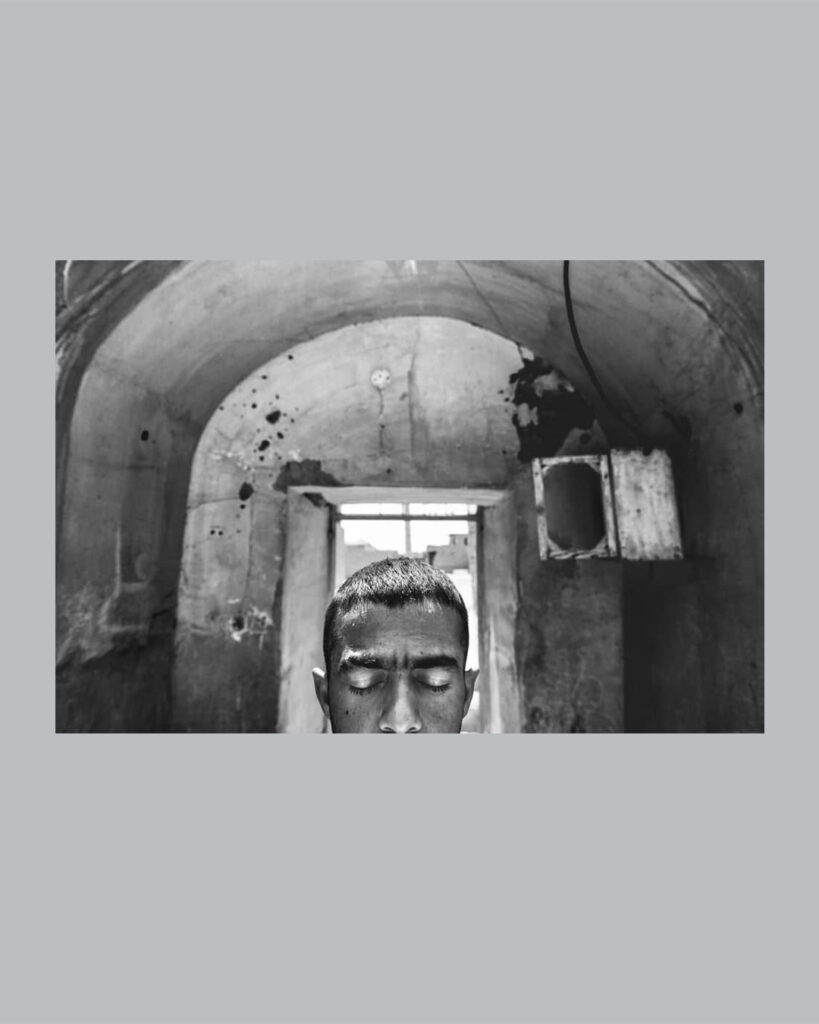

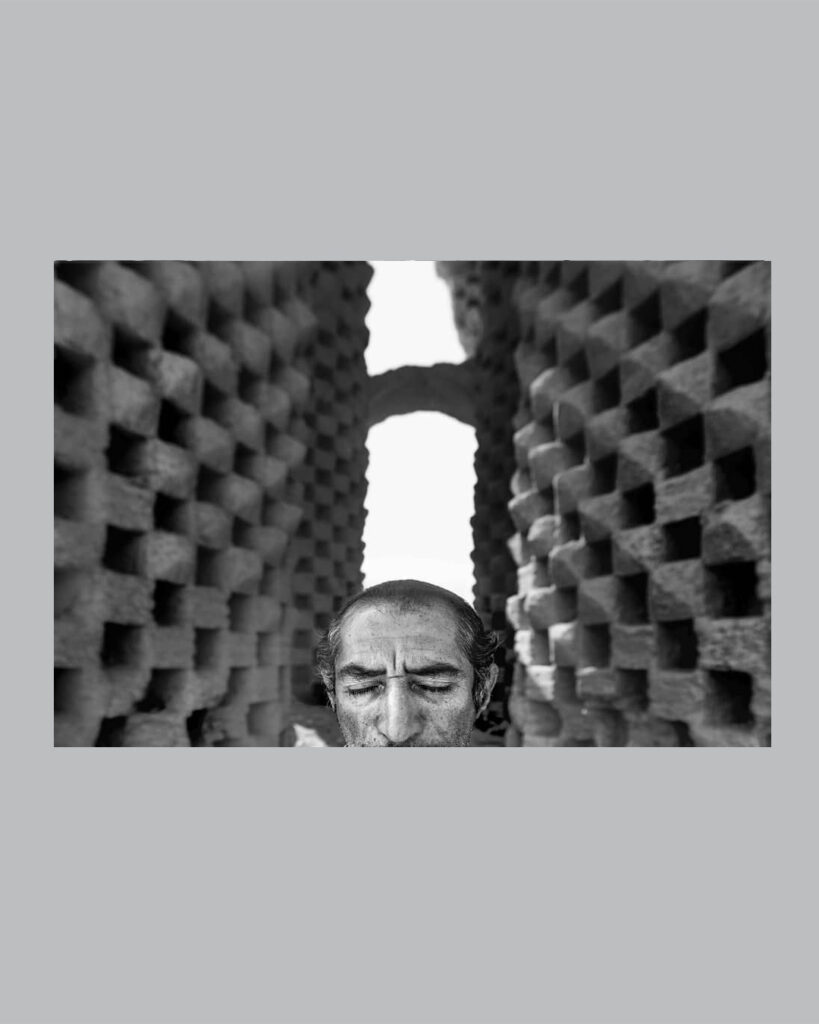

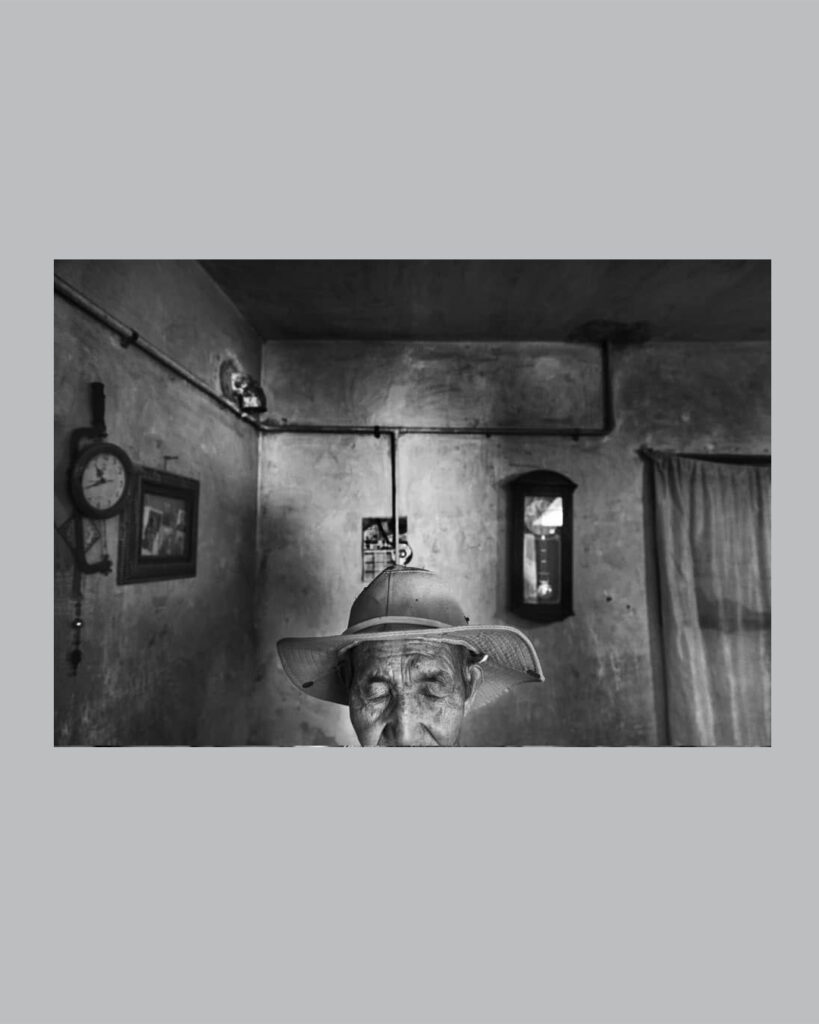

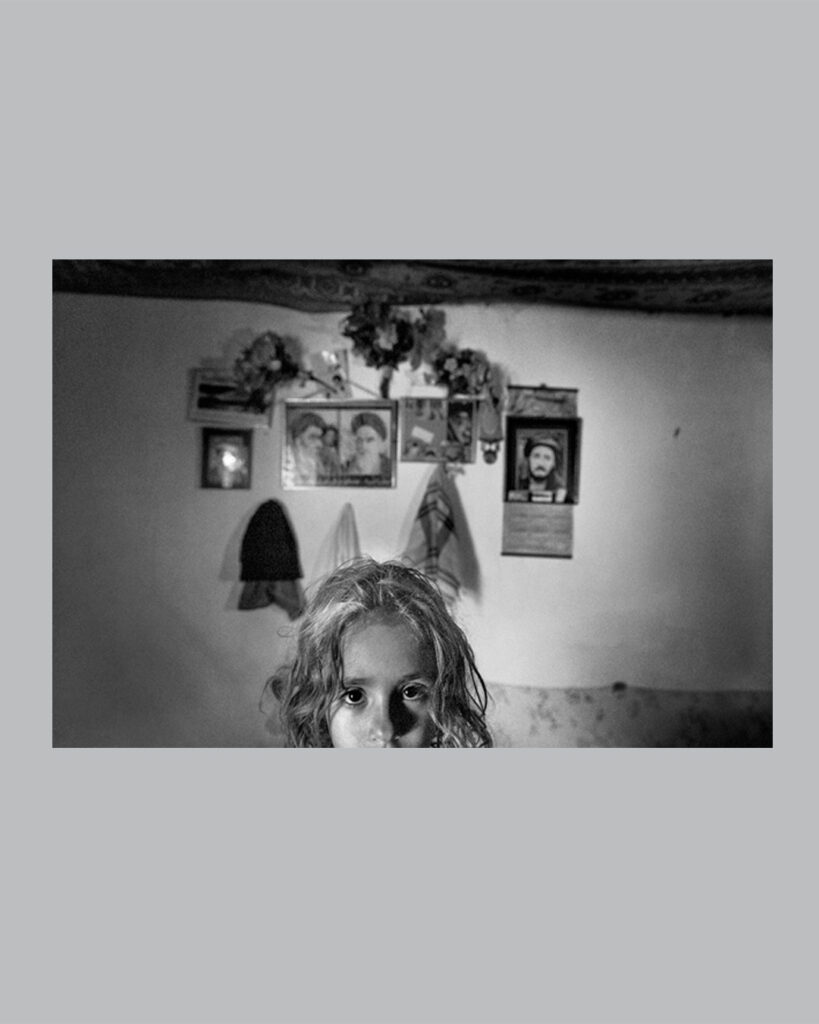

«شکاف» پروژهای است که به بررسی سازوکارهای نادیدهگیری اجتماعی و فرسایش تدریجی زندگی در حاشیهنشینترین فضاهای شهری میپردازد. این سری با تمرکز بر محلهای در شرق اصفهان شکل گرفته و از سطح گزارشدهی اجتماعی فراتر میرود تا به پرسشی درباره اخلاقِ نگاه و شکنندگی حافظه جمعی بدل شود. پرترههای سیاهوسفید با چشمهای بسته، استعارهای از انکار، بیحسی و حذفشدگیاند؛ حذفشدگیای که هم از سوی جامعه اعمال میشود و هم بهعنوان سازوکاری برای بقا درونی شده است. تنها چشمی که باز میماند، کودکِ انتهای مجموعه است که نگاهش نخستین گسست در چرخهی خاموشی و انفعال را رقم میزند.

با حذف زمینههای روایی، تکرار کادر و کاستن از هویت فردی، تصویرها به چهرههایی نمادین بدل میشوند؛ چهرههایی که سازوکارهای ساختاریِ طردشدگی را در خود حمل میکنند. این پروژه مرز میان عکاسی مستند و هنر معاصر را جابهجا میکند و نشان میدهد که چگونه فرایندهای اجتماعیِ «ندیدن» میتوانند در فرم بصری نیز بازتولید شوند.

شکاف در نهایت تاملی است بر مسئولیت جمعی: آنچه در این تصاویر ثبت شده فقرِ صرف نیست، بلکه منطق پنهانی است که به جامعه اجازه میدهد با چشمان بسته به حیات خود ادامه دهد. نگاهِ کودک پایانی، دعوتی است برای گشودگی؛ این احتمال که شاید هنوز بتوان چرخهی نادیدهگیری را متوقف کرد.

فرانک احمدزاده

8 آذر 1403

The Gap: Seeing What Society Learns to Ignore

A Critical Review of Ali Miremadi’ s Portrait Series on Social Erasure

Ali Miremadi is a project-based fine art photographer whose practice unfolds along two seemingly separate yet fundamentally deeply connected trajectories: first, the study of poverty, marginalisation, and the consequences of structural neglect in urban environments; and second, the examination of cultural heritage and the erosion of collective memory under the weight of these very mechanisms of erasure. Working within the visual language of contemporary fine art, Miremadi interrogates the tensions between presence and absence, visibility and disappearance, endurance and decay across human and cultural layers. His theoretical and practical projects, while rooted in lived social realities, move toward a poetic, conceptual and materially reflective mode where the photograph becomes not merely a record of the world, but a site for posing fundamental questions about the ethics of looking and the fragility of memory.

“The Gap” forms part of a broader body of work in which Miremadi turns to marginalised districts and the cycles of poverty and social erosion that shape them spaces where systemic neglect fuels the spread of violence, addiction, and exploitation from early childhood onward. The project began with the artist’s direct engagement with a neighbourhood in eastern Isfahan, on the margins of the airport, defined by high crime rates, ethnic heterogeneity and the overwhelming presence of children growing up within these damaged structures. What started as a collaborative initiative soon evolved into a personal, long-term inquiry that moves deliberately beyond photojournalism, seeking instead to translate lived experience into the language of contemporary art.

Throughout the series, the closed eyes of the sitters’ function as a metaphor for denial, numbness and the mutual invisibility between individuals and the society that abandons them. Only one gaze remains open the child whose eyes turn toward the photographer and toward the future, standing with his back to a past that is visually echoed behind him. The use of black and white reinforces the project’s attention to erosion, shadow, and structural weight; combined with the removal of individual identity and the repetition of formal framing, the portraits shift from representations of specific people to emblematic social figures. “The Gap” is an ongoing project, with portions exhibited at the Fajr Visual Art Festival in 2021.

The visual language of The Gap is built upon a series of deliberate formal decisions, each of which carries a distinct conceptual weight. The use of black and white not only reduces visual distractions and directs attention toward texture, shadow and decay, but also produces a sense of temporal suspension that lifts the portraits out of a specific moment and aligns them with broader structural conditions. The fixed framing and the crop across the mouth strip the sitters of individual identity, rendering them as symbolic figures, faces that seem to belong not to discrete persons but to a collective. This intentional removal of individuality visually recreates the very mechanisms of marginalisation: those denied voice, agency and public visibility appear in the image equally voiceless. Harsh surfaces, limited light and the absence of narrative context construct a muted space in which the viewer’s attention is inevitably drawn toward the eyes or, more precisely, toward their absence. The single open gaze of the child interrupts this visual deadlock, signalling the possibility of seeing, and perhaps the possibility of change. Through these formal choices, Miremadi does more than depict a social condition; he embeds the internal logic of erosion and erasure directly into the structure of the photograph itself.

At its core, The Gap unfolds as a visual meditation on the ethics of looking and the mechanisms of collective neglect. The series does not operate as a social report; rather, it serves as an ethical encounter with an environment where decay, addiction and the gradual dissolution of children’s futures have been normalised. The closed eyes of the sitters become signs of imposed silence and unwilling participation in cycles of abandonment: society does not see these individuals, and they, in turn, have learned that invisibility is a mode of survival. Against this backdrop, the child’s open eyes articulate the project’s only point of rupture a moment in which vision resists the stabilised structures of denial. Through these visual signals, the artist addresses poverty and marginalisation not merely as economic issues, but as psychological and cultural ones in which neglect becomes a kind of social pathology. The Gap, from this perspective, seeks to restore visibility to those pushed outside the frame of public concern while simultaneously inviting the viewer to confront the ethical burden that vision demands.

Encountering The Gap is an experience suspended between observation and involvement; the photograph is not merely a carrier of content but an active determinant of the viewer’s position. The proximity of the frames, the absence of background and the stripping away of narrative markers place the viewer face-to-face with figures who are at once inviting and resistant faces that gradually shift from individuals to embodiments of a social structure. The closed eyes introduce a tension in which the viewer’s gaze slides across a surface that refuses to answer, and it is precisely this refusal that produces a moment of reflection. In this space, the viewer is compelled to experience silence and erosion not through storytelling but through form itself, a form that is simultaneously stark and vulnerable. Within this dynamic, the child’s open eyes become the only point that returns the viewer’s gaze, reopening the possibility of empathy and creating a fissure between denial and hope. Ultimately, the aesthetic experience of The Gap is not passive: the work does not leave the viewer untouched, but places them within a position of responsibility, prompting reflection on their role within the cycles of erasure.

The Gap repositions itself in relation to the traditions of documentary photography, shifting the boundary between social reportage and fine-art expression. Rather than relying on linear narration or descriptive sociology, the artist employs strategies of omission, silence and communicative rupture as formal tools, generating an experience that resonates squarely within the field of contemporary art. Miremadi approaches marginalisation not through the depiction of poverty itself, but through an examination of the mechanisms of seeing and not-seeing mechanisms that documentary photography often overlooks. In doing so, The Gap becomes a body of work legible both aesthetically and theoretically: a project that demonstrates how social structures can be reproduced at the level of photographic form, and how the image may serve as a site of resistance against these very structures. Its significance lies in elevating a social crisis to the level of artistic inquiry, positioning the viewer not as a witness but as a participant in a broader question about collective responsibility, cultural memory and the erosion of human lives at the neglected edges of society. From this perspective, The Gap contributes a distinct voice to contemporary art not as a narrative of poverty, but as a visual study of what must be erased in order for society to proceed unquestioned.

Ultimately, The Gap is less a portrait of a specific neighbourhood than a contemplation of the hidden logic of society: a logic of erasure, numbness and the quiet reproduction of decay. These images do not attempt to resolve the problem; rather, they confront the viewer with a fundamental question: What do we enable and what do we perpetuate when we close our eyes? In this sense, Miremadi’s gaze functions like the open eyes of the child who appears in the final frame an effort to break the cycle of neglect and to assert that hope, before it is an emotion, is an act of seeing.

In the last frame of the series, the child’s gaze is fixed on a point beyond the frame direct, luminous and intentional. Within the logic of the project, this is the first true rupture in the cycle of denial and invisibility. Unlike every figure before him, his eyes are not closed; he is neither trapped in the inherited silence of previous generations nor immobilised by structural numbness. Yet behind him, a dense arrangement of photographs, decorative objects and religious symbols forms a visual field that asserts itself over his life elements that reveal familial memory even as they exert an authority he never chose. This background is not a matter of personal agency but an environment that predates him, surrounds him, and continues to shape the trajectory ahead.

Within this context, the child’s open eyes acquire amplified meaning: he is the only sitter granted the possibility of “seeing,” yet this seeing unfolds within a space where the past, tradition and poverty inscribe themselves across the wall, prefiguring a future that he must either inherit or resist. His gaze, set against this weighty backdrop, becomes both defiance and inquiry a moment of openness within systems that have long predetermined the contours of his life.

The visual identity of this frame rests on a profound contrast: the child’s small, vulnerable body set before a wall crowded with history and command. This tension transforms him into the project’s emblem of hope not an innocent or decorative hope, but one forged in the uneven conditions that surround him. He carries the future, yet it is a future that must navigate the shadow of a past imposed upon him. It is this contradiction that elevates the final image to the conceptual peak of the project: a point at which The Gap no longer articulates the divide between seeing and not-seeing, but the divide between an inherited fate and the possibility of rewriting it.

Finally, the child is not looking toward the viewer to be seen; he is looking so that the viewer might finally see. His gaze becomes an invitation to responsibility: if earlier generations lived with their eyes closed, perhaps this generation still holds a chance at openness if we, too, choose to look beyond our own blind spots.

Faranak Ahmadzadeh

2024 November 28